When junior Frank Vivalda had difficulty feeling comfortable in his identity after repeated misgendering from teammates, his color guard captain had an idea: creating a leaderboard.

It stood in the color guard room, big and white, counting those who gendered Vivalda correctly in a ranking order. As an effort made by the former captain to help him feel better accepted by his peers, Vivalda still appreciates the gesture to this day.

The pseudonym, Frank Vivalda, exists to respect the students’ wishes for anonymity due to fears of transphobia.

Like Vivalda, many other Heritage students have expressed how gender in sports is a serious topic. Several athletes have shared their personal experiences of facing misogyny, misandry, and more: simply because they exist in a field they’re passionate about.

Take the case of senior Xavier Grant, the only male cheerleader at Heritage. Despite the discourse he witnessed in society with male athletes entering ‘feminine’ sports, and the original pushback he faced from his own dad who was fearful of his son “prancing around” if he ever joined cheer, Grant continued.

“I think most males are not very supportive of cheer because they don’t think that people will support them in their decision,” Grant said. “Growing up there were not many people I could relate to that were like me, so it was a little different back then because it just wasn’t as accepting. But if you really like to perform, I don’t think you should listen to [others] because, regardless of my Dad, I was still going to do it because it’s what I like to do. If it’s something you like to do, you should just go for it.”

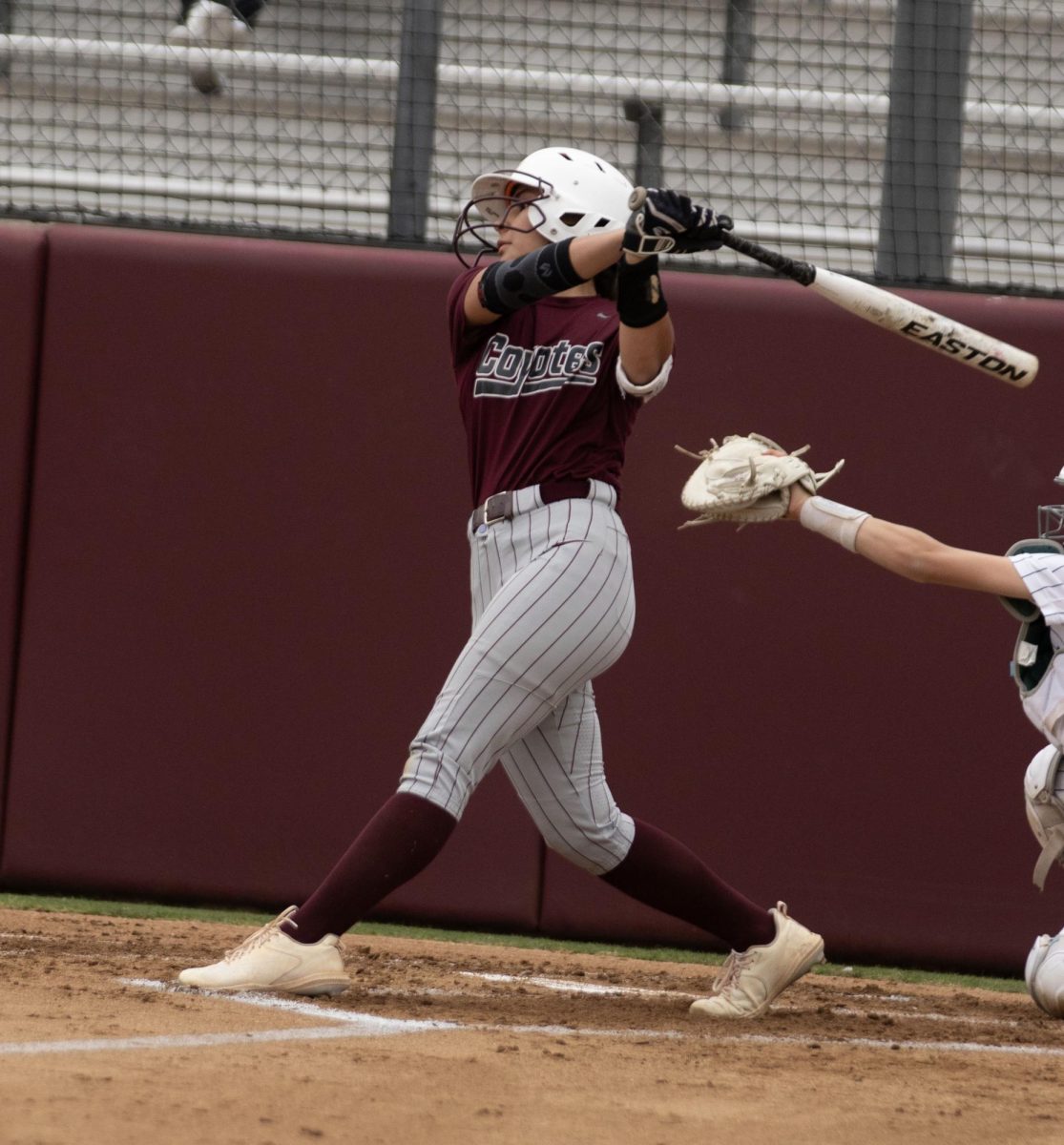

Female student athletes have also expressed discomfort with how the world often views masculine sports and femininity. Brianca Johnson, a junior on the track team, who despite feeling confident in her girlhood and love for sports coexisting, has noticed how the toll these comments have had.

“I think women in sports in general [are] always hypermasculinized,” Johnson said. “I’ve seen people online making fun of Sha’Carri Richardson (a famous female track athlete), saying she looks like a man for having muscles. But she’s just healthy—she has a healthy body.”

In comparison, cheer captain Stephanie Dominguez has shared how often cheer is underestimated as a sport because of its “hyper-femininity” and high concentration of females.

“It can be really stressful and really draining.” Dominguez shared. “‘Put on a uniform, put on a smile,’ well yeah that makes you seem like a cheerleader, but there’s a lot more that goes into it. Like when we put girls up, when we’re tumbling, when we’re jumping—it’s a lot of [mental] and physical battles.”

“‘Put on a uniform, put on a smile,’ well yeah that makes you seem like a cheerleader, but there’s a lot more that goes into it.”

However, in the face of hardship, stands solidarity. And many athletes have expressed the formation of stronger bonds built amongst teammates due to the collective obstacles they face as a group.

Sophomore Aditi Seshadri, who’s on the swim team, describes an experience where she met other female athletes and had the opportunity to “really connect over experiences [they’ve] had in the sport as girls” and eventually grow better as a group.

Color guard captain Vivalda, ensures his own teammates never have to feel uncomfortable to be themselves in the practice room. Though ‘Frank Vivalda’ was created to respect the athlete’s wishes to stay anonymous due to fears of transphobia, Vivalda actively utilizes his own experiences in guard to speak out on the treatment of trans people in the media and more so the sports industry.

“I think they are scared,” said Vivalda. “[For example,] in the media, gender-affirming care is called ‘the mutilation of bodies,’ and they use these big scary words to instill fear into people.”

This fear has often manifested itself into real-world policies. Last year, Tennessee governor Bill Lee passed a bill stating that high-school transgender athletes will have to “prove” that their sex matches the one listed on their birth certificate, with added penalties for those who don’t comply. Tennessee has also been working on a bill that would ban transgender athletes from participating in women’s college sports. According to PBS News, both proposals are expected to clear the General Assembly.

Similarly, Texas has passed bills restricting trans youth from access to any transition-related medical procedures, and for those who were in the middle of such treatments to be “weaned off” in a “medically appropriate” manner. Along with this, bill HB 25 has been signed, which requires trans-student-athletes to play on the team that aligns with their assigned gender at birth, and bill S.B. 15, which outlaws transgender college athletes from playing on the team of the gender they identify as.

“They’re scared of trans women in the girl’s locker room, trans athletes in sports, they’re scared of what’s different,” Vivalda said. “But statistically speaking, how many trans women want to do volleyball so bad? There are [some] in Tennessee and they’re banning it completely because they’re so scared of these [few] individuals. [But] if we could get over that [and] accept the trans athlete: her whole life could turn around. [As] now, she’s a girl fighting in a girl’s sport, and that can do wonders for people.”

In response to the argument often made by the opposing side, of biological advantages being present for trans athletes in a sport, Vivalda offered a solution. He said that those obstacles can be talked about and found accommodations for, instead of immediately reacting to ban trans people completely.

Many minority athletes undeniably face discrimination. According to statistics by KickItOut.org: last year, athletes of color faced a 279% increase in online abuse, female athletes faced a 400% increase in reports of sexism, and Islamophobic/sectarian chanting on the courts increased by 300% and 15.8% respectively. However Vivalda, like many Heritage athletes, has expressed feeling safer in their sport than in other aspects of life. A feeling that many students only hope can become the norm instead of the exception, societally someday.

“Every time I walk into guard, I feel like I can be myself,” Vivalda said. “I feel like these people not only respect me, but they care about me. And it’s really, really cool. It made me realize how much I love not hiding, because I feel like I’m home when I walk onto that practice field, that I can be myself and everyone is comfortable with it. I [have] a home there. I have a part. I absolutely recommend.”