Speechless

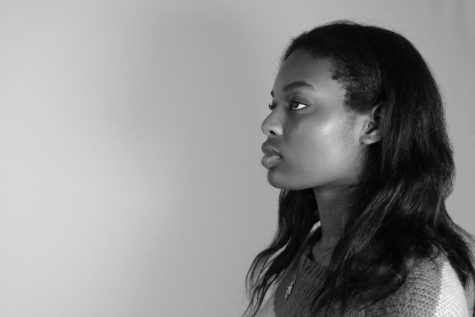

Alexa Abusomwan finds her voice through her native language

February 21, 2023

The air inside the room is thick with nostalgia. Family members meet after years apart. Numerous things might have changed, but one thing’s always constant: language. Seeing her family converse in their native language, junior Alexa Abusomwan feels left out of the lively discussions. To her, it’s just a jumble of words.

“I really want to learn my native tongue, but it’s a struggle,” Abusomwan said.

Abusomwan, who’s of Nigerian descent, has tried to make efforts to learn her native language, Edo. The biggest challenge, however, is the limited resources available.

For those who are of a different culture than the majority, speaking one’s native tongue serves as a way to strengthen family ties. Especially after being apart from family for a significant amount of time, practicing ancestral traditions is a way to reunite and catch up.

However, for younger generations living in the States like juniors Mya Kivindyo and Olivet Adeyemi, it’s become difficult to learn their culture given the lack of exposure.

“Language is so important in our culture and that’s one thing we really wish our parents have focused more on teaching us how to speak,” Junior Mya Kivindyo said. “You see your family members talk in your native language and you feel a little bit left out.”

Living in a country away from your ancestors can limit the amount of exposure to cultural practices, affecting younger generations’ knowledge of their heritage.

“My grandma used to be a teacher in Africa, so I had to take all those books and learn myself,” Abusomwan said.

Kivindyo also believes that having someone over from your motherland can help reinforce lost cultural practices.

“Having grandparents from your motherland come stay with you definitely helps because they’re also from an older time,” Kivindyo said. “They followed more traditions and know the language better than our parents who have now lived in the states for so long.”

Besides family, engaging in community events also stimulates better connections between one’s culture and identity.

Abusomwan, a regular attendee at her church, enjoys participating in cultural activities.

“There is a church that I went to with all Nigerians. They have a panel, where we can ask questions about our culture,” Abusomwan said.

Despite the physical distance from her home country, Abusomwan is able to bridge the gap by fostering close friendships.

Adeyemi, one of Abusomwan’s friends, is grateful for the strong bond between them.

“Being from the same continent and finding similarities between her culture and our parents and the way we were raised is heartwarming,” Adeyemi said.

The bond that they have nurtured has allowed them to recognize the shared disconnect from their respective languages.

“That’s the thing with immigrant parents. They did not teach me [Yoruba],” Adeyemi said. “I understand what they say, but I only know a few words and phrases.”

Kivindyo believes it’s up to the parents to prevent this temporary disconnect from eventually becoming permanent.

“Parents who have kids here in the States, they need to start speaking to their kids,” Kivindyo said. “They actually need to start sitting down with them and teaching them these languages.”

Looking at the future, Abusowmwan wants to make sure her native language continues through later generations.

“Since I can’t speak my native language, I want to make sure my future children will be able to speak, so it doesn’t go extinct or anything,”

Given the several obstacles to practicing cultural traditions away from home, it’s evident that Abusomwan and her friends are determined to preserve their language for generations to come.

“Words are everything to people and society,” Kivindyo said. “When your language is dying out, it’s almost like a part of your identity is being lost in the world.”