We the People

As today’s youth becomes more involved in the political process, the legal age to vote should reflect it

November 17, 2020

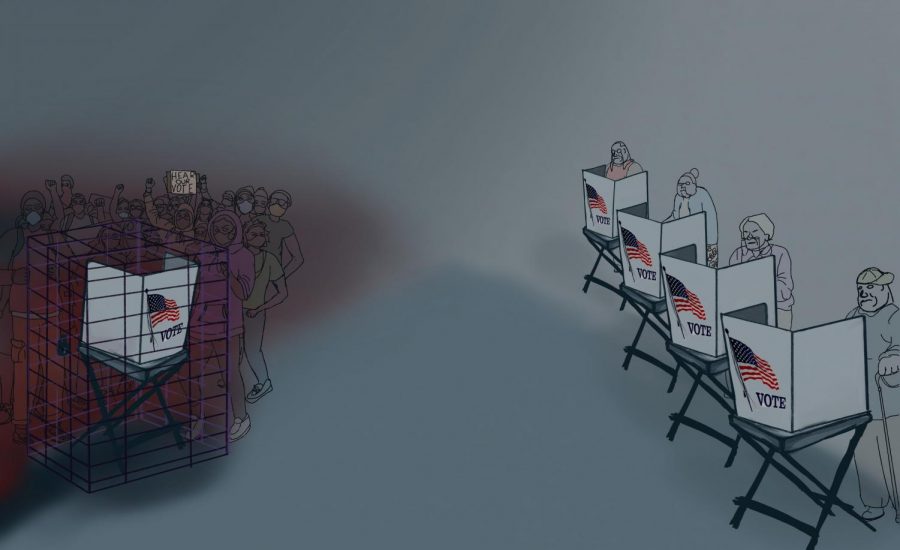

At 16, you can automatically be tried as an adult for certain felonies. At 16, you can obtain a license to operate a vehicle. At 16, you gain medical freedom to decide what is best for your health. But at 16, you can’t vote. At 16, you can’t vote for the leaders that hold the power to grant or take away your rights at the drop of a hat.

We all know the basics of American democracy, but let’s have a short refresher. Democracies derive their legitimacy through consent of the governed. Consent is expressed by voting. Subscription to a system in which decisions are made about us but not with our say is inherently undemocratic. Elections always affected teenagers — now we just want the right to influence the policymaking process.

This isn’t a new argument either. Our history is laced with social movements that aimed to broaden the definition of democracy to be more inclusive. Suffrage was expanded from white men with land (1789), to all white men (1856), to men of all races (1870), to women (1920) and finally to 18-year-olds (1971).

The unifying theme linking these movements together? Each effort was condemned as too radical for its time. Until it wasn’t.

Silent, but always significant

Lowering the voting age to allow 16 and 17-year-olds to vote has been a silent, yet significant debate that has dominated local politics for several decades. Already, 13 states have introduced bills that would grant suffrage to a whole new electorate, but not Texas.

We can already hear the outcries:

“But high schoolers are too immature!”

“They don’t know enough to be able to vote!”

“Why would we let kids decide the future of our democracy?”

Except that’s not true.

Time and time again, we’ve seen national social movements take shape from the grassroots efforts of youth. The anti-war protests of the 1960s. The environmental justice movement. The recent Black Lives Matter protests.

All of these movements featured widespread student mobilization and leadership. Clearly, we are mature enough to unite around a common cause and force change. Clearly, we have taken steps not only to educate ourselves but to translate that information into real-time action.

And while we’re on the subject of education as a prerequisite for suffrage, I didn’t know we were imposing restrictions on who can vote based on how informed they are. If that’s the case, then adults should be subject to the same scrutiny.

At this point, most of us are aware that Facebook is far from reliable when it comes to factual information. Yet 43% of adults report that they get their news from the same social media site that has come under intense scrutiny for its role in spreading misinformation in the 2016 election cycle. That certainly doesn’t sound like an “informed” voter.

Students on the other hand, are discouraged from using social media. In fact, we are taught in school how to research sources, think critically and verify information through reputable sites.

Glitz and glamour

It’s also true that local elections lack the glamour that is associated with national races. National races like those for the Senate, House and Presidential elections are given much more media attention. Increased coverage, in turn, creates the misconception that national races are more important than local elections.

In reality, however, it is our state, county, city and district officials who make the decisions that are — literally — closer to home.

Funding for that extracurricular activity you work so hard for? It’s our school board who is responsible for securing it.

More mental health resources available to you on campus? The school board has to support funding for those resources.

Not only does voting in local elections ensure that student issues are being addressed, it actually increases future voter turnout. In a country where less than half the population between the ages of 18 and 29 voted in the last election, clearly the importance of voting is not emphasized enough.

Voting is a habit. Like any habit, it’s more likely to become a repeated behavior if established during adolescence. Empowering 16 and 17-year-olds to vote in local elections instills this behavior in a whole new generation, making it more likely that they will be an active member of our democracy for years to come.

Speaking of our democracy, ever heard the phrase “no taxation without representation”?

America was founded on the principle of representative government — the principle that if you pay taxes then you are entitled to elect the officials responsible for raising them.

Around 20% of high schoolers are employed, meaning that 20% of high schoolers pay some form of taxes. Seeing as 16 and 17-year-olds are the ones providing government officials with their paychecks, they should have a say in electing them.

This election cycle saw an unprecedented number of youth use their power at the polls to make a decisive statement: we are here, we will vote, and we will not be ignored.